“What comes to your mind when you hear ‘The Future of Work’?” This is a question I often pose to learners. Most respond with some apprehension, and usually with the phrases: “automation and machines”, “need to reskill”, “robots and programming” and the most pertinent one: “fear of tech taking over our jobs”.

This is not the first time that the world has experienced such changes or technological disruptions. The switch from using typewriters to computers in school and at work over the last few decades is a good example of this change. So how did workers over the years acquire the skills needed to use new technology? What lessons can we learn from the past to help us be better prepared for what is about to come? How can we be equipped to take on transformed jobs in the future of work? These are some of the questions that inspired me and through the course of my research, I have the privilege of engaging with learners, workers and union leaders, and many have shown their adaptability and resilience in overcoming the fear and anxiety to seize the opportunities brought about by the current technological disruptions.

Learning from the past

Students at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) have the opportunity to learn more about the impact of the Industrial Revolutions and technology on society and workers through various courses offered under the core curriculum. Indeed, when we identify the characteristics of the First, Second, Third and Fourth Industrial Revolution (Industry 4.0) in class, the continual change in the man-machine combination and its effects on the nature and design of work is most evident to the students.

The First Industrial Revolution saw the advent of steam engines and machines capable of mass production, especially in the manufacturing of garments, to reach a larger consumer market. Ironically, workers became i less skilled when they were tasked to perform more specific functions such as using machines to sew a specific component of garments. The Second Industrial Revolution, anchored on electricity, enabled even greater mass production and communication. Interestingly, workers—such as those working in the car assembling factories— needed more technical skills even as they become even more specialised.. The Third Industrial Revolution however, marked a significant difference in the way work was designed and done. The use of digital technology allowed us to harness the processing power of computers in areas from manufacturing to information technology and communications and as well as achieve other complex functions. Unexpectedly, this digital shift increased efficiency and production, and workers are required to have the adequate digital skills to work with computers.

As many have noted, Industry 4.0 was predicted to, and has changed the way we approach work. While Industry 4.0 (and 5.0 that has already taken place in some local sectors) share similarities with the first three industrial revolutions, the stark differences between them and Industry 4.0 need to be appreciated and understood so that our graduates and workers can stay employed and employable and also, have the capacity to seize the opportunities that the future of work brings.

We can see that while technology in the Fourth Industrial Revolution also enables production at a large-scale similar to the first two Industrial Revolutions, Industry 4.0 shares elements of the Third Revolution in terms of using digital technology to carry out tasks more efficiently.

Industry 4.0 is unique in the sense that not only can it utilise technology to complete routine, mundane, and even dangerous tasks (such as port crane operation and surveillance), it can also establish patterns from big data in different industries, whether in healthcare, finance, retail or advanced manufacturing. Take for example, in the accounting industry, technology enables the auditing of all transactions for the detection of anomalies and discrepancies. This frees up the accountant to take on a higher-value role in sense-making and advising on the steps to rectify the identified issues, allowing for more effective human-machine collaboration. In the Fourth and even Fifth Industrial Revolution, the human-machine relationship is one of complementarity with companies utilising technology to handle the mundane and dangerous tasks, such as using drones to conduct surveillance of tall structures, while workers evolve to one of providing insights, being the domain expert and strategic partner alongside the technology. Now, equipping of workers means enabling them to harness the technology to value-add to their domain knowledge and expertise.

Acceptance of technology

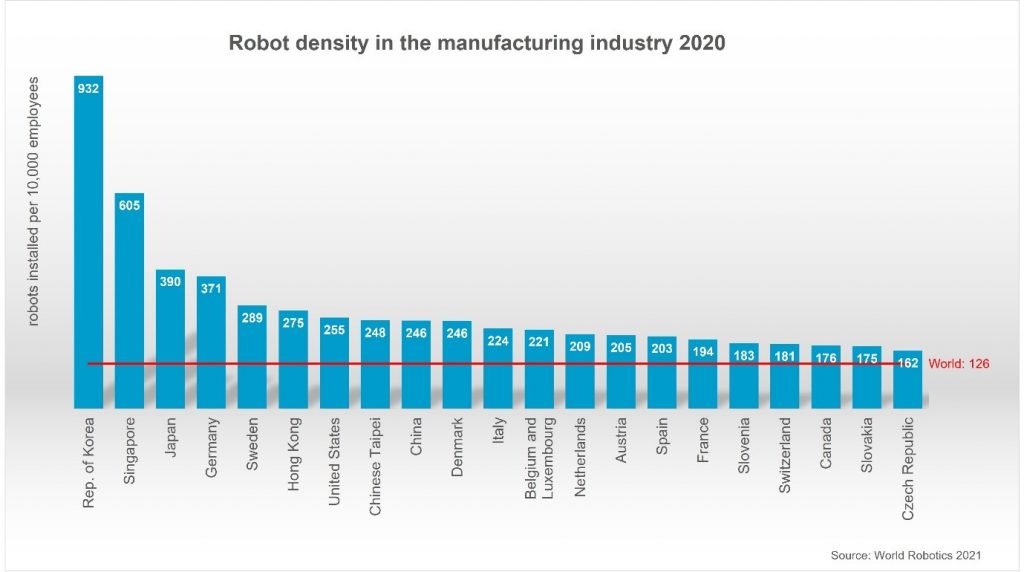

Not all economies however, have the same perspective of technology adding value to production or complementing the role of the worker. The acceptance, or conversely, the aversion to technology depends on whether an economy embraces technology or strongly opposes is directly related to the labour supply of the country. In countries where there is manpower shortage, for example South Korea and Singapore, the acceptance and adoption of technology in labour-intensive sectors such as waste management, has been positive (MSE, 2022). It is therefore not surprising that these countries have the highest robot density in the world (International Federation of Robotics, 2021).

Conversely, in countries such as India and the Philippines where there is an over-supply of workers, certain sectors that are heavily reliant on labour have been resistant to technology adoption. This was observed during the regional fieldwork conducted as part of the research on employment and workforce skills undertaken by SUSS’ Centre for Applied Research and the Ong Teng Cheong Labour Leadership Institute together with the International Transport Workers’ Federation. The aversion is two-fold: firstly, the fear that the technology would replace workers: such as the tap-entry card making the bus conductor redundant for example; secondly, the concern that workers would not have the skills for the new technology and hence be irrelevant for the new roles.

Equipping workers for the future of work

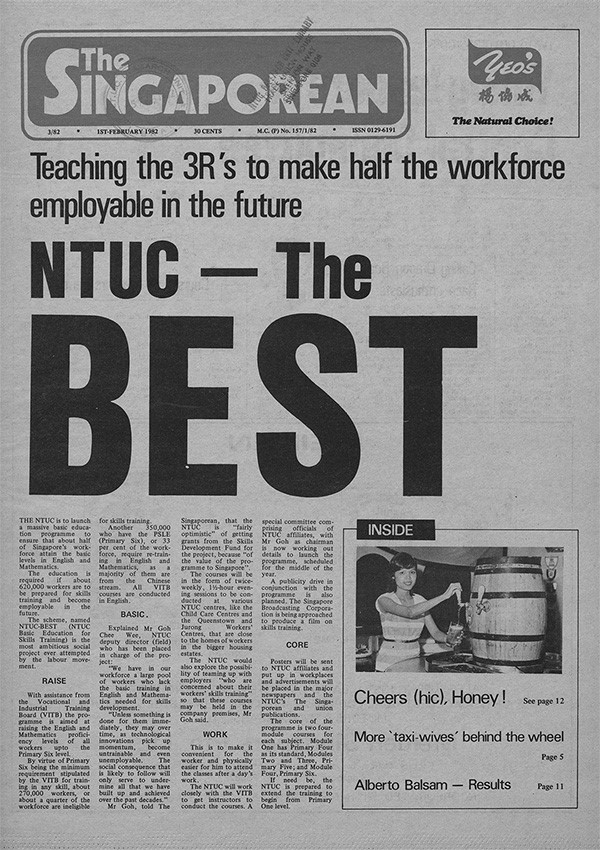

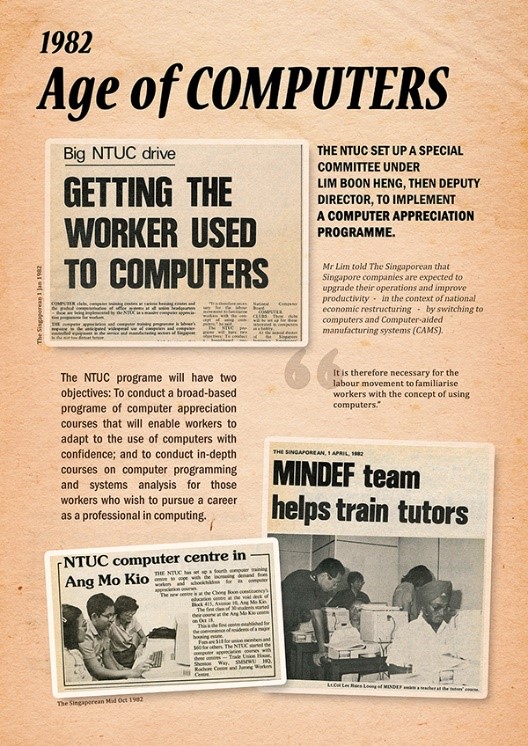

The need and impetus to prepare workers for the changes in technology though is not new. In Singapore, programmes to upskill and reskill workers to adapt to the use of computers were already taking place in the 1980s.

Source: NTUC, 2019, Reunion: Celebrating our past. Inspiring our Future. Training and Re-training the Worker, ReUnion – Marking the Birth of a New Labour Movement

In 1982, the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), together with the Vocational and Industrial Training Board, initiated a programme to raise the English and Mathematics proficiency level of workers to Primary 6 level so that they could embark on further skills upgrading. The skill that workers at that time needed to learn was none other than basic computer operation and programming.

So we can see that even though the need to upskill is not new, there is always some degree of inertia, discomfort and even complacency when the requirement to reskill and upskill arises. In this regard, the role of union leaders in Singapore is often underappreciated and unnoticed even though they encourage and mobilise workers to prepare for transformed jobs. Behind the scenes, they are the sensors, key mobilisers and influencers on the ground, nudging workers to be equipped with relevant skills. When there were downturns in the past, union leaders were at the forefront to help companies save costs, increase service standards and productivity through initiatives such as committing workers to the Skills Programme for Upgrading and Resilience programme to acquire certification and formal qualification in areas such as Aerospace, Human Resource, Electronics Engineering and Information & Communications Technology, and even to recover from the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008.

Unions in Singapore continue to support workers as they reskill and upskill to keep up with technology-enhanced services in sectors such as finance and healthcare. One example is of a bank teller who, despite having no prior computer knowledge, benefitted from the strong encouragement of her union leaders as well as her colleagues to complete rigorous training and took up a transformed role as a video teller (National Trades Union Congress, 2019)

From the above, we can see that the first step to equipping workers is identifying the skills and the relevant training for the transformed roles within an organisation. One such key initiative is the Company Training Committees (CTCs) which brings together union leaders and senior management of the company to map out career paths and the required upskilling and reskilling for employees. The CTCs initiative received further support in the recent Budget 2022 with $100 million set aside to scale up the CTCs.

We should do well to remember that work transformation in Singapore is not confined to Multi-national Corporations. Indeed, it is encouraging that Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have taken steps to adopt technology and at the same time, their workers have seized the opportunities to upskill and reskill. This is particularly important as SMEs employ about 70% of Singapore’s local workforce (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2021).

Although SME employers are acutely aware of the impact of future of work and the need to prepare their workers, they face day-to-day challenges of business sustainability such as ensuring that costs are covered and customers’ orders are fulfilled. Hence, the role of the SME “boss” is crucial in taking the lead to upskill and reskill themselves. One example is Mdm Ang, director of Hong Seafood, a local seafood supplier, which received a May Day Award in 2018 for fostering a culture of learning and upskilling. She recognised that attending courses to learn new management skills and market knowledge would encourage her staff to do likewise. True enough, her employees began to attend courses that enabled them to use technologies such as a warehouse management system and a customer relationship management system and were able to transform their work (Hong Seafood, 2017).

The future of work brings about challenges and anxieties, not dissimilar to those experienced in past Industrial Revolutions. Yet, while routine and dangerous tasks will be automated, the Fourth and Fifth Industrial Revolution offer opportunities for workers who reskill and upskill to work alongside the technology and to bring their domain expertise into higher-value roles. Union leaders and progressive SME employers continue to lead by example and workers who respond positively reap the benefits from the future of work.

References

Hong Seafood, 2017, Keeping Up with the Times

http://hongseafood.com/2017/07/27/keeping-up-with-the-times/

International Federation of Robotics, Dec 2021, Robot Density nearly doubled globally,

https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/robot-density-nearly-doubled-globally

Ministry of Sustainability and Environment (MSE), June 2022, Towards Zero Waste Singapore

https://www.towardszerowaste.gov.sg/zero-waste-masterplan/chapter5/

National Trades Union Congress, 2019, NTUC’s Future Jobs, Skills and Training Forum 2019 Summary Report

NTUC, 2019, Reunion: Celebrating our past. Inspiring our Future. Training and Re-training the Worker, https://reunion.ntuc.org.sg/1980s/

Singapore Department of Statistics, April 2021,

The European Sting, May 2019, What the Fifth Industrial Revolution is and why it matters, https://europeansting.com/2019/05/16/what-the-fifth-industrial-revolution-is-and-why-it-matters/