When I started my research project in Kampung Peneleh, Surabaya, I was convinced that it should be a dynamic research that involves local academics, students, and residents of the neighbourhood. The project is one out of the six study sites under the Southeast Asia Neighbourhoods Network (SEANNET)[1], which had stipulated the necessity of an engaged research since its inception in 2017. Community-engaged research here refers to an examination of issues that affect the community’s well-being, with active involvement of community members and organisations in collaboration with academic researchers. Community-engaged research in SEANNET aims to read cities differently: While boundaries of social, cultural and economic life of cities in Southeast Asia remain porous and continuously changing, administrative boundaries still dictate policies and studies of the city. These urban policies and studies are led by dominant actors, such as governments, developers, and technocrats, which tend to reflect the elite rather than the ordinary people. The everyday experiences and relationships in the city (Figure 1), which are more representative of urban life in Southeast Asia, are under-represented in formal knowledge as well as in urban policies.

Figure 1. Urban neighbourhoods in Southeast Asia, such as Kampung Peneleh, are significant in the historical formation of urban settlements in the region and in the cities’ contemporary urban life.

Community-engaged scholarship still faces criticisms, which contribute to the reasons for resistance, as follow: power inequality between researchers and community partners[2]; contradiction between practical application and theoretical-conceptual expectations;[3], perpetuation of local social inequalities by going through a gatekeeper or local leader to access the community;[4] and potential conflicts of interest as community partners have their own agendas to push[5]. Furthermore, the “grey areas” between research and advocacy in community-engaged research may exposure researchers or their assistants more to the threat of data integrity, as they face the pressures of meeting the quota for research subject recruitment, all the while knowing that time is required to build relationships with local communities [6]. Besides these epistemological and ethical concerns, academic bureaucracies too present as obstacles. Scholars have pointed that tenure criteria are rarely in favour of community-engaged scholarship in academic institutions[7].

Conducting community-engaged research is not easy. Academics are required to maintain ethical relationships with the community. Even as they gain the trust of the community and gain deeper understandings of their needs and concerns that can help them to formulate relevant research questions, academics must ensure contacts remain professional rather than personal. Academic researchers also need to see communities as active subjects who can continuously interact with and shape the research project. This includes factoring in some flexibility in the research project; not just in terms of methods and activities, but also as far as regularly revisiting the objectives to ensure that the research remain relevant since everyday experiences in the community can be quite dynamic.

Kampung Peneleh features many aspects as a neighbourhood with the potential to contribute to building knowledge on cities in Southeast Asia. At a glance, it looks like other relatively old kampungs[1] in the city. In fact, it is one of the oldest kampung in the city of Surabaya – the second largest city in Indonesia – but it is still largely missing in urban studies in Indonesia. Besides having multi-generational residents that can possibly share their memories, Kampung Peneleh also has interesting features in its built environment, such as a European-style mosque, house architectures from different periods since the 19th century, as well as alleyway graves that date back to the 18th century. Kampung Peneleh is adjacent to the Kalimas River, part of the Brantas River system that connected Surabaya shores to the Majapahit Kingdom in the 14th century (Figures 2, 3 and 4). It is also next to a Dutch cemetery from the colonial period (Figure 5). In the late colonial period, Kampung Peneleh was also the place in which several nationalist movement leaders received their education. Among them were Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, Musso the leader of Indonesia’s Communist Party in the 1940s, as well as Kartosoewirjo[8], an Islamist movement leader. In spite of these thick layers of history, the kampung remains an ordinary neighbourhood full of contemporary social and cultural activities among its residents. With these important aspects of the neighbourhood, it was obvious that a comprehensive research had to involve various disciplines.

Figure 2. Location of Surabaya in Indonesia (base map by Uwe Dedering 2010, location sign by author)

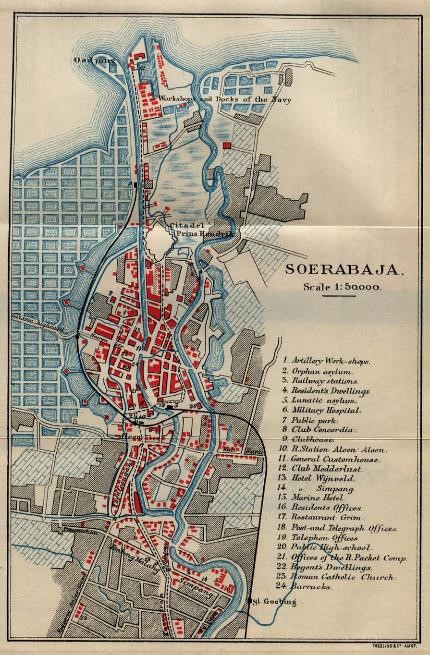

Figure 3. Surabaya map in 1897. The map did not mention Kampung Peneleh, but it shows Peneleh’s location as an urban settlement along Kalimas River (Source: Map of Surabaya, Indonesia, from Guide to the Dutch East Indies by Dr. J.F. van Bemmelen and G.B. Hoover, Luzac & Co, London 1897).

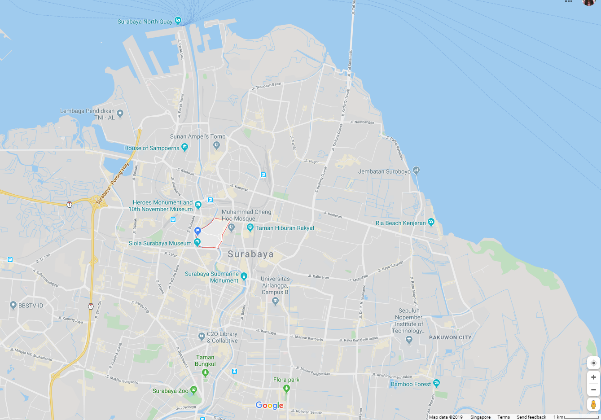

Figure 4. The location of Kampung Peneleh on current map (Source: Google Maps, 2019).

There are at least three parts in examining Kampung Peneleh in Surabaya as part of SEANNET: 1) research; 2) pedagogy; and 3) community project. These three parts are applicable to all SEANNET study sites to link research with teaching and action. All SEANNET research projects, including Surabaya, examine the neighbourhoods based on commonly shared core research questions: What has been happening to neighbourhoods in cities in Asia, why does it matter, and for whom does it matter? The role of the local PI is thus very important to make deep community involvement possible. In our case, Kampung Peneleh was recommended to us by our local PI, Adrian Perkasa, a historian from Universitas Airlangga in Surabaya. Having been active in community involvement since his undergraduate studies, Adrian’s familiarity with Kampung Peneleh enabled us – together with him –to form a research team involving interested students. These students were recruited intentionally so that the team can work on constructing new urban pedagogy from the neighbourhood.

The team’s presence in the neighbourhood introduced the community (from leaders and residents to students) to the SEANNET research project. After one year of introduction, , the research team solidified to rely on two undergraduate student research assistants and collaboration with community architects. One of the two students lived in Kampung Peneleh by second half of the second year, and the other intensively visited the neighbourhood.

Figure 5. Dutch Cemetery at Peneleh (Source: Author, 2019)

Figure 6. Children’s football at the Dutch Cemetery (Source: Author, 2019).

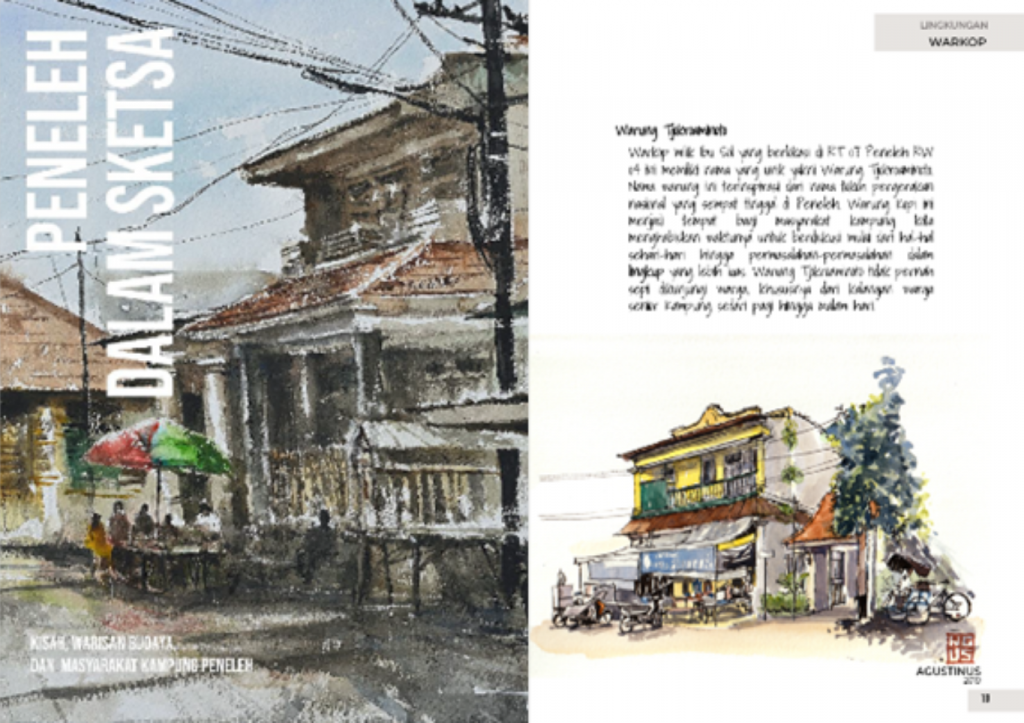

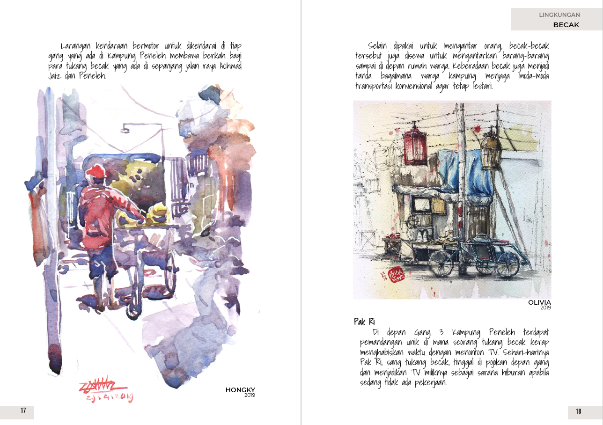

After two years of ethnographic research, the team and the community identified a project to bring the research findings outside academia. Sparked by exchanges and a library visit at a workshop in Chiang Mai, another SEANNET study site, the community architects in the team suggested to document meaningful places and activities in Kampung Peneleh in a sketchbook. The community welcomed the idea and eventually the research team collaborated with Urban Sketchers Surabaya to conduct public sketching sessions at Kampung Peneleh from April to May 2019. The sketches from these activities are documented in Peneleh Dalam Sketsa (Peneleh Sketchbook)[9], a collection of sketches and stories that are based on academic research findings (Figures 9 and 10). The public sketching activities (Figures 7 and 8), university-community events, as well as connections between the research team and the community are examples of various approaches in community-engaged research that can grow gradually and dynamically from the relationship between researchers and communities.

Figure 7. Sketching the process of making kroket, a local snack (Source: Author, 2019).

Figure 8. Interaction between Urban Sketchers Surabaya members and Kampung Peneleh children during a public sketching event (Source: Author, 2019).

The experience from SEANNET research at Kampung Peneleh is very rich. Firstly, it illustrates the challenges faced in community-engaged research: to be open to projects that are of interest to both the community and the researchers. Most research grants do not have this flexibility, but the openness to pedagogical and community project components in the SEANNET grant from the Luce Foundation enabled the research team to include community engagement in the Surabaya programme.

Figure 9. Cover page and a sketch from Peneleh Dalam Sketsa (Cover sketch by Daniel Indratama, 2019; Warung Tjokroaminoto sketch by Agustinus Angkoso, 2019; text by Eka Nurul Farida, Muhammad Rohman Obet, Adrian Perkasa and Rita Padawangi, 2019; layout by Arkom Jatim, 2019)

Figure 10. Sketches of becak, a traditional transportation means, from Peneleh Dalam Sketsa (Sketches by Hongky Zein, 2019; Olivia Tanzil, 2019; text by Eka Nurul Farida, Muhammad Rohman Obet, Adrian Perkasa and Rita Padawangi, 2019; layout by Arkom Jatim, 2019)

Secondly, Kampung Peneleh study reflects the challenges that have been identified in previous criticisms of community-engaged scholarship. The scale of the neighbourhood is relatively smaller compared to the usually large administrative boundaries of the city, and the study of smaller neighbourhoods is meant to challenge existing formal understandings of the city territories. Yet there remains wide scepticism of in-depth research within smaller boundaries in the study of cities. In terms of the local situation, the research team was always aware of the existing local inequalities as well as the gatekeeper phenomenon, and work to avoid perpetuating local power domination.

Thirdly, embedding the research team into the community is a meaningful exercise, but there are at least a couple of ethical issues to keep in mind. One, not all findings can be published. Some sensitive stories may have to stay within the neighbourhood, because publicity may jeopardise the well-being of those involved. Two, once embedded in the community, the team has to be prepared for a long-term commitment. A quick exit from the field is undesirable, as such approach treats communities as study objects. On the other hand, the team is also aware that residents understand that the research project has a timeframe, and are likely to be open to the process of transitioning out from the community when it is completed.

Last but not least, community-engaged research at Kampung Peneleh demonstrates the importance in connecting research interests with realities on the ground. An issue as mundane as knowing our own neighbourhood and its people may be more complex in the context of contemporary urban life. In particular, the questions on why a neighbourhood matters and for whom it matters point to social and political inequalities. A community-engaged research induces appreciation toward the various layers of urban life. These layers are important in understanding the city, configuring its development for the future, as well as in contributing to building city knowledge from Southeast Asia.

[1] self-built urban settlements with interrelated social, economic and cultural relationship

[1] The Southeast Asia Neighbourhoods Network (SEANNET) is a four-year research and pedagogical programme, funded by the Henry Luce Foundation and is administered by the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS). The author is the Regional Coordinator of the programme.

[2] Gala True, Leslie B. Alexander, and Kenneth A. Richman, “Misbehaviors of Front-Line Research Personnel and the Integrity of Community-Based Research,” Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 6, no. 2(June 2011): 3-12.

[3] Doug Brugge and Alison Cole, “A Case Study of Community-Based Participatory Research Ethics: The Healthy Public Housing Initiative,” Science and Engineering Ethics 9, no. 4 (November 2003): 485-501.

[4] Emily E. Anderson, Stephanie Solomon, Elizabeth Heitman, James M. DuBois, Celia B. Fisher, Rhonda G. Kost, Mary Ellen Lawless, Cornelia Ramsey, Bonnie Jones, Alice Ammerman, and Lainie Friedman Ross, “Research Ethics Education for Community-Engaged Research: A Review and Research Agenda,” Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 7, no. 2 (2012): 3-19.

[5] Anderson et al., “Research Ethics Education.”

[6] True et al., “Misbehaviors.”

[7] David G. Marrero, Emily J. Hardwock, Lisa K. Staten, Dennis A. Savaiano, Jere D. Odell, Karen Frederickson Comer, and Chandan Saha, “Promotion and Tenure for Community-Engaged Research: An Examination of Promotion and Tenure Support for Community-Engaged Research at Three Universities Collaborating through a Clinical and Translational Science Award,” in Clinical and Translational Science 6, no. 3 (June 2013): 204-208.

[8] Pronounced as: kar-to-soo-weer-yo

[9] “Peneleh Dalam Sketsa” expected publication date: year 2020.